by Gary Chapman

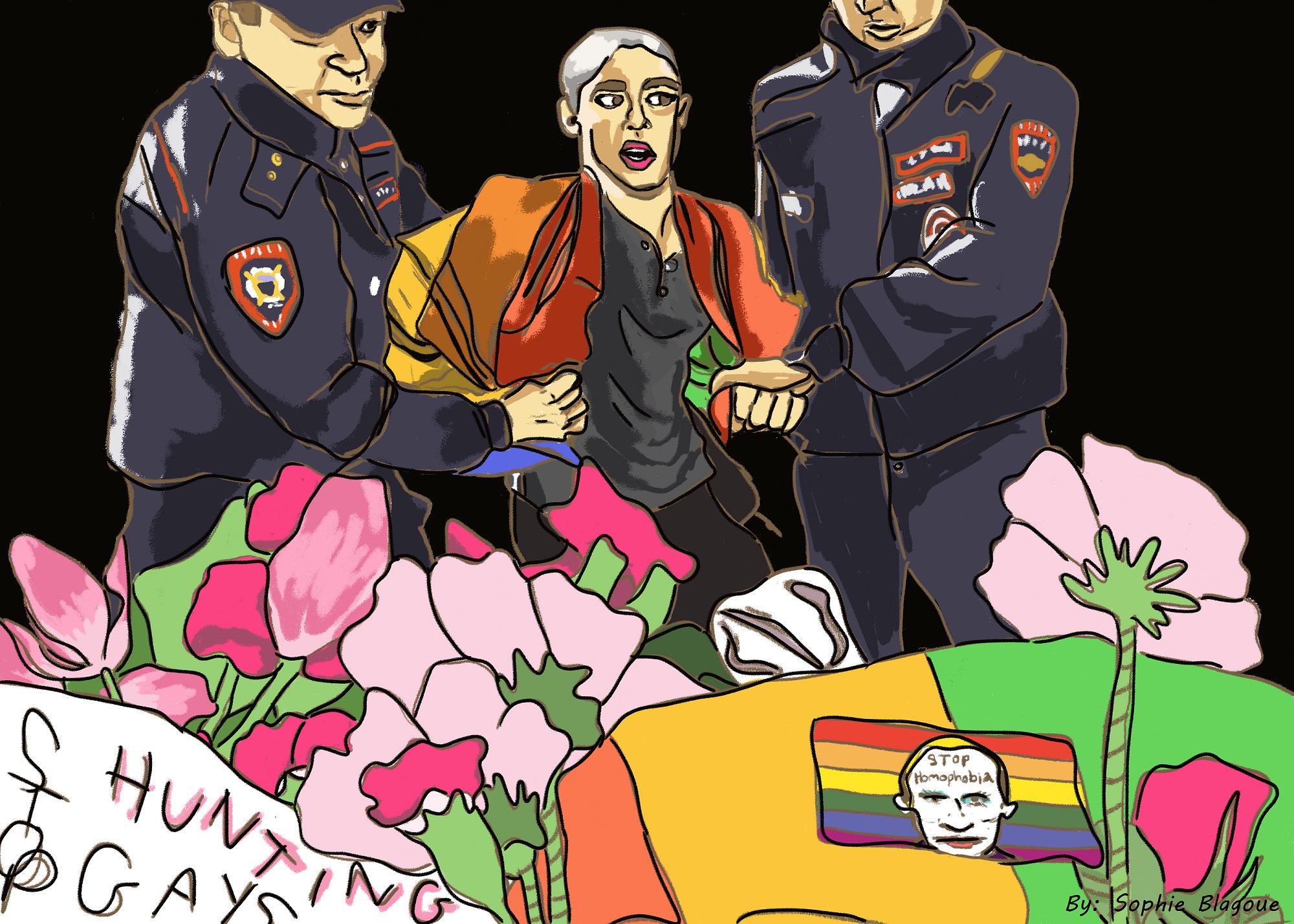

On Aug. 8, 2017, up-and-coming Chechen singer Zelim Bakaev was walking in the city of Grozny while in the area for his sister’s wedding. According to credible eyewitness accounts, he was allegedly grabbed by security forces and pulled into a van and was never seen in the flesh again. Now, what could he have done to cause him to be pulled into a van by the Russian equivalent of Seal Team 6? Apparently, according to local activists, the crime was being gay.

Chechnya, a fairly autonomous area of Russia, near the border of Georgia, is run by Ramzan Kadyrov, who was appointed by Vladimir Putin in 2007. The gay purges started being talked about in 2017, when Novaya Gazeta, a local opposition paper, reported that over 100 men were detained and tortured, and that three were killed in Feb. 2017.

One of the major examples is Maxim Lapunov, an events planner who was arrested and beaten by police in March 2017. Maxim went public about his experience in October.

According to Maxim, The police would “burst in every 10 or 15 minutes shouting that I was gay and they would kill me [and] then they beat me with a stick for a long time: in the legs, ribs, buttocks and back. When I started to fall, they pulled me up and carried on.”

When the allegations were brought up to Kadyrov in July by David Scott for Real Sports, he claimed that the reporters are, “devils. They are for sale. They are not people. God damn them for what they are accusing us of. They will have to answer to the almighty for this.”

He also said to Scott that, “We don’t have those kinds of people here. We don’t have any gays. If there are any, take them to Canada [and that] Take them far from us so we don’t have them at home. To purify our blood, if there are any here, take them.”

This is also backed up by Alvi Karimov, a spokesperson for Kadyrov, who said to Interfax, “If such people existed in Chechnya, law enforcement would not have to worry about them since their own relatives would have sent them to where they could never return.”

Chechnya also has a history of killing denouncers as well. Anna Politkovskaya, a reporter for Novaya Gazeta, was murdered in 2006 after being critical of Chechnyan officials and Putin. Alexander Litvinenko said, in his goodbye note, that, “You may succeed in silencing one man but the howl of protest from around the world will reverberate, Mr. Putin, in your ears for the rest of your life. May God forgive you for what you have done, not only to me but to beloved Russia and its people.”

In 2020, a film titled Welcome to Chechnya was released, which documents the efforts of people who ran safehouses for LGBT Chechnyan people and Maxim, who for most of the film was deepfaked along with others. The film also showed the effort they did following a person named “Anya” by the filmmakers.

“Anya” is/was the daughter of a high-ranking Chechnyan official who was discovered to be a lesbian by her uncle. She fled, thanks to the organization, and was moved to a safehouse somewhere in Eurasia. When she took a walk, after being isolated for about six months, she went missing and was never found again.

Russia, Chechnya specifically, does have a history of “honor killing.” Kadyrov said that, “If we have [gay] people here, I’m telling you officially their relatives won’t let them be because of our faith, our mentality, customs, traditions. Even if it’s punishable under the law, we would still condone it.” And that just says a lot.

On Feb. 9, the European Court of Human Rights declared that urgent matters must be taken in regards to the case of Salekh Magamadov and Ismail Isaev, who were kidnapped at the beginning of the month in Moscow.

The Chechnyan officials, according to the Russian LGBT Network, charged them with “complicity with illegal armed groups”, and, initially, no family, lawyers or other officials were allowed.

What can you do to help this? While there has not been a purge since 2019, you can still look at and maybe donate to the Russian LGBT Network, which can be found at lgbtnet.org.